Updates From the Ceramic and Design studio of Christopher St. John

in which the artist writes about his life and practice...

Hello and welcome to the second edition of my newsletter. The date is May 25, and the weather has been delightful here in Athens, Ohio. Spring storms have been moving through the region over the last several weeks, their water feeding the forests that cover the hills of Wayne National Forest, and the evening frog choruses have been sublime…Thank you to all the new subscribers to this newsletter. I appreciate you and the time you spend here. If I didn’t make it clear before, for now, this newsletter will be published every other week. As my subscriber base grows, I am looking at different ways to make this interesting and enjoyable. As my readership grows, I can look at weekly offerings. Although I don’t know how it is for you, I only have so much time to read (and write) all the things, so I want to make sure this space is intentional and respectful of all of our time.

ANNOUNCEMENTS

Adamah Ceramics in Columbus will be hosting my one day artist talk and demo on June 8 from 11am -3pm. I will be giving a hand-building demonstration and talk about my approach to sculpture in clay. I will also talk about my background as a 2d artist and how that informs my current practice, creating connections between art and living on a garden world. Expect lots of excited blabbering about exoplanet discovery! I can’t seem to stop talking about every new development in this exciting field. (K2-18b anyone?!) What does this have to do with clay? Come by the gallery on June 8!

Additionally, this should be a great weekend to be in the Short North Arts District in Columbus with the Columbus Arts Festival happening June 7-9.

My work is being featured in the June issue of Ceramics Monthly Exposure section. This is the third time I have been lucky enough to have my work featured in this publication. Check out my little rabbit plate at the Ohio Designer Craftsman Best of 2024 Exhibition. Julie Ellen Byrne and Quinn Hannah (one of my former students) are some of the awesome ceramicists featured in this exhibition. This exhibition always surprises me, and I was really honored to be included this year.

FROM THE CLAY STUDIO

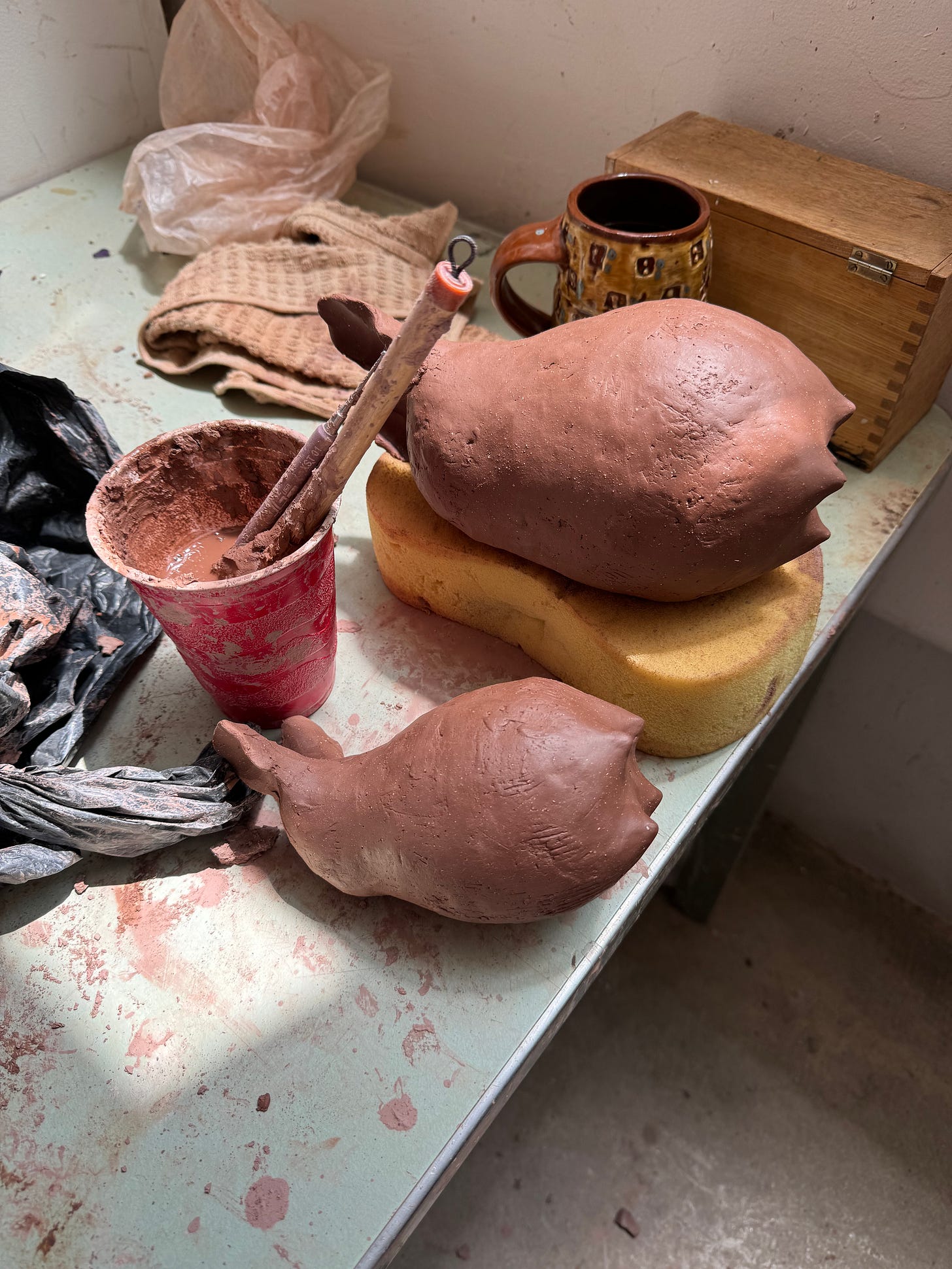

Sumatran Rhino-earthenware, slips, glazes, digital photo, original animation, original field recording, 2024

Back in December, I was very lucky to receive a commission from a woman affiliated with the breeding program working to repopulate Sumatran Rhinos. Although she tells me that the effort to save the population at this point is largely unsuccessful, I believe that the people involved in this work are incredibly proud of their efforts to save a really beautiful animal. Sumatran Rhinos are shy and sensitive animals who need large areas of uninterrupted forest to live and thrive, and unfortunately, only about 40 remain in the world. I don’t write that to pin blame on human animals as evil, but the systems that incentivize habitat destruction in favor of trade continue to expand. From the World Wildlife Federation website entry on the Sumatran Rhino:

“Sumatran rhino habitat is being lost or degraded by invasive species, road construction, and encroachment for agricultural expansion. for example, Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park in Sumatra is losing forest cover due to conversion for coffee and rice by illegal settlers.”

Before graduate school I loved any opportunity at making rhinos, and this commission offered me the chance to revisit an old friend. They are fantastic animals to sculpt, with super interesting bodies and textures, and we are lucky to still be living in a time with populations of megafauna.

FROM THE DRAWING STUDIO

The Argentinian composer Dario Duarte and I have begun work on our second collaboration together. The project is currently called LATITUDES (working title), and explores shared spaces of a collective interiority. Dario (his preference for pronunciation is like “Mario”), based in Buenos Aries, is currently composing the music and creating the sound work. I have finished all the keyframes for the animation that will be a part of this project. We don’t have a time line in mind, but potentially we are looking to launch this next spring 2025 during my second solo show at Adamah Ceramics with another iteration at the University in Buenos Aries.

I am pretty excited by this project and having a chance to work with Dario again.

I am also spending more time in my drawing studio, which means I get to make work like this:

These drawings are done in ink and clay and oil stick. I use a nib pen, brush, and stick for my pen and ink work. The appearance of the bull and the minotaur and folding the portrait back into my animal forms augers an exciting period of transition. It feels weird to write (and maybe dated ) but the shadow of Picasso has always hovered over me. As a painter, I became aware of Picasso’s ceramic work after I learned about the clay cultures of indigenous peoples of the Americas, and somehow, in the way that Picasso always seems to do, I felt excited and cheated all at once by the ubiquitous Spanish artist. Envy is never a good motivator. I always tell my peers and students to have the courage for their own ideas, but Picasso the dragon took so much of the art historical hoard for himself that I didn’t mind following his back trail a little to find my own way in clay. All of this new drawing work is preparation for my solo show at Adamah Ceramics in October.

(For what it is worth, Georgia O’Keefe and Lee Bontecou were as much primal influences on my artistic practice as Picasso. I like edges and frictions zones.)

FROM THE BOOKSHELF

The Confessions of St Augustine

In this small book from the early Christian writer, St. Augustine meditates on his life in light of his piety and faith. His reflections on death and his relationships to women make this a timely read. The cadence and tone of the work feels very similar to the kind of spoken monologue I keep on my nightly walks in the forest, which surprised me, and I feel an affinity with this writer’s attempts at positioning a sense of the spiritual in our living relationship to the world. I would call this space prayer, but E.O. Wilson’s work The Creation: An Appeal to Save Life on Earth is the model which I think is a beautful answer to St. Augustine’s queries about the nature of the world. Wilson addresses the faithful in his book and asks how religion can be a model, alongside science, for healing on the only garden world that we currently know. The question I ask myself constantly: how can the artist’s vision better support an actively engaged and healthy model for living with life on this world?

FROM THE FOREST

Frog choruses sound like the stars. Their songs twinkle in ribbons of color and pulse like starlight. It is easy to imagine, walking the trail next to the river at night, that these animals, generation after generation in their emergences and meetings and matings, in the work they do as community partners and as beings on this world, have some generational understanding of the presence of starlight and moonlight. The nights I prefer to walk are the ones like this month’s flower moon, when you can see the interplay of silver on water and get a sense of the lay of their habitat as they sing across acres and acres, each clutch and each collective in living relation to other clutches and collectives across habitats. They live and die in the arc of the season under this radiant procession of the cosmos. Frogs do their best work in regulating insect communities and help keep that engine vital, and they also serve as indicators of environmental health. The current chytrid fungal blight that has been wiping out as much as 30 percent of global frog populations has meant that communities that used to hear these spring choruses no longer hear them. And that means, in some way, the stars no longer hear them. The universe itself can no longer listen in the way that it once did when species disappear and go silent. Whales are built to utilize and experience sound in such long distance ways that can feel cosmic in their scale, and it is hard not to hear the glimmering of starlight in each peep and echo of peep in frog song. Does the universe evolve life as way to sing its vastnesses closer, to echo each clutch of life on other garden worlds? Do rock and ice sing to rock and ice, as Mercury and Pluto might echo each other?

AFTER-PART 2

When Studios Die…

The American potter maestro George Ohr was something of a veritable wizard of clay, a peculiar combination of American grit and huckster ingenuity that was the original mold for all the wonderful American West Coast weirdness of ceramics that later emerged in the 1960s. He was based in Biloxi, Mississippi and his daring visionary forms combined pots into future/past amalgamations of twists and lifts that really had no precedent. His handle energy alone is worthy of mention here, catapulting and vaulting into the space surrounding his pots like the original Minoan bull dancers, forms that Ohr brought to audiences on the simple magic of really great hands, wit, and a kick wheel. There was a magic to what he crafted and audiences grudgingly admired his unique contributions to the history of ceramics.

But Orh’s studio burned to the ground, leaving only the kiln. The fire began at a local saloon and destroyed many of the buildings in the town. By this point in Ohr’s life, he had not only lost his studio but he had also put two children into the same earth that gave up its magic so easily to his talented hands.

As I finished my semester and packed up the sunlit studio that marked the fourth clay making space I would occupy in my ceramic career, Ohr’s story kept returning to me. His prankishness, his sense of fun, and that sense of optimism and mirth that I associate with folks like Walt Whitman and Ken Kesey’s merry pranksters, people who seemed like they would be good friends in better times. More importantly, it was his willingness to continue his practice and adapt in the face of adversity that I held close.

I have had four studios under clay. The first was in a haunted basement in an old house in Portland, Oregon, one that initially served as my painting studio before I broke up with oil paints and the figure. The house, coincidentally enough, was also partially lost to fire at one point in its history, leaving only the old brick chimney. Similarly, my basement studio was lost to flood and the fire of a passionate relationship that would be the center of my ceramic life for the next four years. In the basement studio, I read Paulus Berensohn and made pinch pots according to his approach and philosophy, sometimes in the nude. Berensohn was a former professional dancer, and I admired the way he positioned the body as central to one’s relationship to clay. Clay is about movements, movements of water and energy and gravity and the mud that becomes stone under the right conditions. Later in grad school I would meet Nicole Seisler and Lalana Fedorschak and these connections to Berensohn and the path of the body’s movement in clay would ring again, reminding me of the truth of this chosen path.

In that basement studio I made unfired pinch pot after pinch pot. Lining the shelves with 4 ounce balls of clay, I practiced with the intention of existing without ego between the relationship of weight and the eventual outcome of the form. I learned to capture nuances of the material, understanding its language of push and squeeze, the earth manifested as clay in my hands. I bought my first clay from Georgies in Portland, experimenting with different kinds of earthenware clays. I didn’t yet understand that all these clay bodies were formulated by shop techs into different clay products. For me it was all a kind of mysterious magic, some gritty, some smooth, some smelling like rivers, some just smelling like old dirt, and some sweet in a space existing between nostalgia and growth and loss. I was really entranced, all the while navigating questions like “when are you going to throw?” from concerned friends. I knew the first time I touched clay that I was a handbuilder, but I didn’t yet know how to articulate that to an audience that was just as ignorant as I was of this practice. Nor did I understand that this is a dichotomy that still haunts ceramics and in my opinion, prevents a lot of useful innovation (potters vs sculptors, a match-up for the ages.) I prefer hand building because it put me in direct unmediated access to the material in a slow way, metered by rhythmic movements of the hand across the building of walls and the shaping of surfaces. Hand building is romantic, and I am okay with that.

None of these pinch pots were ever fired, and the flood turned them and all the books and painting and other pieces of my life into mud.

Later, I shared a studio with the woman who had ignited this newfound passion for clay. It was a place of sunshine and song and dancing and quiet and love, and we worked side by side in a converted garage that served as her studio and which she courageously invited me into and into her practice and life. Paulus’s teachings stayed with me. She and I danced in clay together, and I learned to make the animals that I decided would replace the figurative work that I had spent such a long time developing. I wanted to access immediate joy again and long summer strides and a feeling of peace. I learned I could live a life in clay. The steel table that I used in that space I still have, but the relationship is gone.

I didn’t know I would be marooned in Ohio. Graduate school was meant to be a temporary assignment and a pathway to a better life, my contribution in the swimmer’s strokes that would power something new and dynamic forward. As I worked in the studio space at Ohio University that I referred to as “The Fishbowl”, my third ceramic studio in my career, I wondered if I would ever see Oregon’s douglas firs again.

Working in The Fishbowl was important. In that space, I learned how to make my clay practice public. I also failed. A lot. The breakup did a weird thing to my brain, and I quite literally forgot how to make anything in clay when I arrived at graduate school. Nothing made sense to my hands, and I had to rebuild something that didn’t look like the clay thing that had existed and sustained me before school. Studios are also places to be captured and to be reborn in. And in the fishbowl, through one exploded work after another, I crafted a new ceramic artist to replace the old one. The space of The Fishbowl was long and narrow, like a coffin for a giant. Not enough space to walk around the work, but with a bank of windows that provided the best lighting of all the spaces in the grad program. I remained in that space for two years, working many hours at the expense of a meaningful social life. The light was consistent and the space was not too hot in the summer, but it was humid. The occasional squirrel got in through the window I kept open to ventilate the odors of my witches brew, a continuous vat of reclaim clay that I experimented with all kinds of materials in my clay bodies. I wanted to better understand the aging process in iron rich clay and how various organic materials affect that process. The spring of my second year I turned the entire classroom studio into a stinking barnyard by adding local grasses to my witches brew…a smell to remember. (Thank you methanogenic bacterium!) This space welcomed me day in and day out, happy or sad (is he crying again? I heard my studio mates whisper to each other that first semester as I sculpted animals and wept).

In my final year of school, I moved into the big boy studio referred to as The Pit, my fourth clay studio. Moving into this space meant that I had earned a spot in which to do the serious work that I came to graduate school to do. Good light, and I finally had space to walk around to walk around the work and to understand how large ceramic pieces in color function in large spaces. Working in The Pit also provided me with an opportunity to see what I needed to have a functioning ceramic studio outside of school that would meet my needs. Small needs like a table to make pots and sculptures, and enough floor space to get on my hands and knees to work the clay from the ground up and into space. Also wall spaces to put up that never ending flow of drawings and paintings that a ceramic practice could not kill. Kilns, of course. And most importantly, the thing I came to graduate school for, connection to community in the mentorship relationships that I sustained with my undergraduate and graduate peers as an educator. The Pit served many of my clay needs, and I was able to manifest the reality of the person I had nurtured in three long years of study and hard work. I made lots of work there. And when The Pit was empty, I could play metal as loud as I wanted.

What are clay spaces? Ohr’s first studio functioned like a mystical repository of fantastic energy that set the stage for the studio he rebuilt after the fire. Any artist knows that there is an accumulation of intention and energy that makes studio spaces feel like combinations of labortory and meditation chamber and museum. Sometimes torture chamber if you are a painter like Francis Bacon. But unlike painters like Bacon, ceramic artists need space and community that function together in some meaningful way. Ceramicists gather and do. Sometimes they do their work alone, but their work exists in linkages of shared labor and equipment and materials that have allowed the practice to evolve over the 30,000 plus years that we know of clay’s persistence in the evolution of human culture. Graduate school meant for me developing my practice as artist/teacher. Like Ohr’s studio, each iteration of clay space I have inhabited has meant something of a dying and rebirth, a place where I have set aside one inhabitant of this self and replaced it with another. And like Ohr’s whimsical reconfiguration of form, I have had to use these spaces to reinvent myself in one acrobatic manifestation after another. Clay is expansive in its nature, and clay spaces that center a ceramics practice are spaces that invite this expansive growth and rebirth. However, as I step into the world and begin to make plans for my new studio, I turn to the natural world for a useful reminder as to why studios exist in the first place. Birds don’t live in nests. They build nests to raise new offspring, to put their genes into the future and ensure their song and their kind continue, in the hope that ideas like robins and morning doves survive in this world. These are linkeages of lived communities of which birth is a small part. Birds in fact live in trees, in the air, in meadows and thickets, buildings and telephone wires and highway underpasses. As I move forward and think about the new studio I will have in the fall, this is the lesson I have learned working in all these studio spaces: that this artist’s life and the studios that sustain it are meant to serve, so that these ideas and connections may continue into the future and survive. I create so that I may live and teach and bring others into this muddy fold…

To be continued!

Please drop me a line if this work speaks to you, or if you have suggestions on things you’d like to see. This newsletter is meant to give you a window into my creative life and as such represents an offer of friendship. I am grateful for you being here and welcome the opportunity to listen to you. If the work and the writing speak to you, please consider a paid subscription. Your support means I can do this small work in sharing my creative work beyond the studio and the gallery. Going forward, your support means I can open a new studio in the fall to manifest the projects I am excited about, and that I believe you will be excited about, too. We need more intentional connections to model leadership and risk-taking and community building with the many community partners on this garden world. Currently, paid subscribers receive a small ceramic sculpture as my expression of gratitude, and I am looking at other ways to make this readership experience richer and fuller. See you in two weeks.

All the best,

Christopher